An opinionated deep dive into local forgotten cemeteries, asylums, and deinstitutionalization.

A Frenchman online called it “walking with providence” – just heading out, guided only by intuition and motivation. This concept has clearly passed down to me through my Quebecois and Belgian roots, serving as a decent excuse for my wanderlust. Having a sense of adventure and desire to experience new things without an endpoint in sight has led me to many places, one of which is the Massachusetts State House.

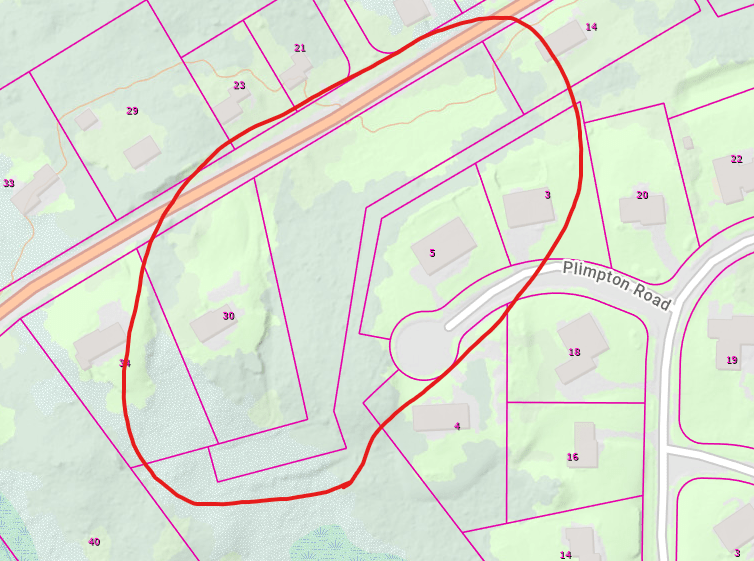

Yesterday I was tasked with a research project for a bill that aims to sell off a parcel of state-owned land. The Foxborough State Hospital has been out of service for decades, and piece by piece it has been sold off to local developers. One of these plots is on the far end of the property, squished between residential zones and hidden beside the woods. The State Hospital’s cemeteries lay here, undisturbed and unmaintained. Through a combination of resources, MASSGIS, MACRIS (as pictured), and several news reports I was able to figure out the odd history of these cemeteries and others belonging to now defunct state hospitals. Before diving further into the cemeteries, it is important to understand the history behind Massachusetts State Hospitals and their ultimate closure in the late 20th century.

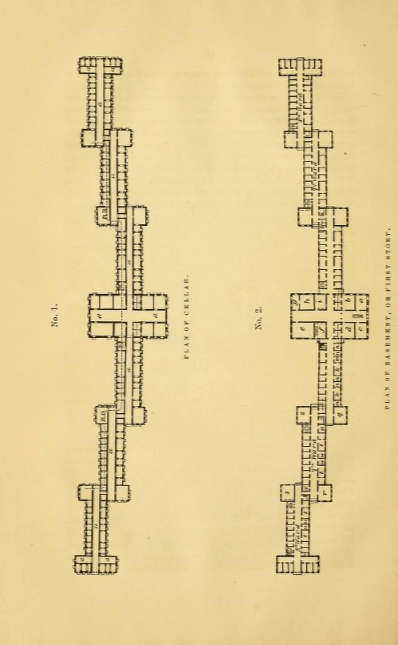

I am a firm believer of environments determining a person’s ability to grow and develop. The space that someone occupies is a reflection of their both identity and potential, just like the way someone dresses is how they present themselves to world therefore how they subconsciously view themselves. As modern philosophies for psychology and sociology were first developing in the mid-19th century, physicians were working to find cures for the issues people faced. Thomas Story Kirkbride was a psychiatrist practicing in Pennsylvania who believed that mentally ill patients were not a burden to be stored away and forgotten, but individuals who could be treated. He took a much more humane approach, focusing on the well-being and development of the patients. In his 1854 treatise On the Construction, Organization, and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane with Some Remarks on Insanity and Its Treatment he strongly details his perspective on beating the issues that plagued mental hospitals of the time and providing genuine treatment to society’s most vulnerable. This book provided the foundation for what is now known as the Kirkbride Plan, a blueprint for the physical and social construction of mental care facilities in America. This plan preached the values of a constructive-oriented environment for the patients, spacious and comforting, while giving each individual group spaces and a personal space. There was a heavy focus on providing sunlight and airflow to patients, which Kirkbride believed could aid the healing process. Routines were strict and staff members were encouraged to live on the premises for the betterment of the patients’ care. These revolutionary ideas manifested in a number of hospitals across the United States.

Branching off from the linear ideas of Kirkbride, the Cottage Plan developed. Instead of the organized single-building structure that his blueprint advocated, the Cottage Plan instead opted for a more decentralized and natural environment that had various buildings sprawled out over a larger mental care campus. Foxborough State Hospital and Medfield State Hospital were both designed with a hybrid of these two psychiatric philosophies in mind. Starting off as the Massachusetts Hospital for Dipsomaniacs and Inebriates with authorization from the state legislature, the Foxborough State Hospital stood strong for nearly a hundred years.

State-run facilities across America drifted away from the Kirkbride Plan due to unsustainable costs and growing administrative burn-out. Asylums became overcrowded, staff lost enthusiasm, and patients became neglected. This went against the entire philosophy that started off so strong in the 19th century. Conveniently, as proper Kirkbride-minded hospitals became too expensive to keep running, the medical community started advocating for at-home care and increased medication. Deinstitutionalization began in the early 20th century and these cost-saving measures eventually led to the full closure of numerous mental hospitals around the nation. This act left desperate and vulnerable people at the mercy of their communities, leading to financial dependence on the public rather than the government. I must admit my bias, I think this was a boneheaded decision to shift responsibility and prioritize finance over the well-being of the disabled. The Foxborough State Hospital would formally close in 1975, scattering patients to the wind like leaves during a windstorm.

These properties were left in limbo for decades, with the Foxborough State Hospital finally starting redevelopment in 2005 with the demolition of a section to build a shopping plaza. The main campus building and its immediate surroundings have been turned into both commercial and residential rental units, giving new life to the space. Vestigial parts of the campus remain undeveloped, still in the same peculiar state since the 70s. The State Hospital’s cemeteries, just like the long-forgotten patients, seem like an afterthought. Finding the exact location of the cemeteries was a surprising challenge because the property, across from the Patriot Place / Gillette Stadium property, is without a defined street number. Even the surrounding properties had oddly designated street numbers on different sites. It felt like trying to read a written message that someone just erased, having to squint your eyes to guess what the letters are.

The property itself is given a confusing marking on the Massachusetts Interactive Property Map website (MASSGIS, my love!) which makes the story much more ambiguity. I had to do a lot of research to understand the land use jargon; the Property Type Classification Codes document from the Bureau of Local Assessment was a lifesaver. The State Hospital’s cemeteries are listed with the land use code 919V, while other local cemeteries are listed as 953V and 953I. I have come to understand that the “V” vs “I” distinction at the end implies either “vacant” or “improved” land, but this is something I would need to contact the town assessor to confirm. This document lists use code 919 as “Other, Commonwealth of Massachusetts – Reimbursable Land” while 953 is classified as “Charitable, Cemeteries”. This classification system has only led me to more confusion, because how can a cemetery be either vacant or improved? There are corpses there, we’re not going to pave over them and plant down a new Market Basket.

The biggest concern I have is the fact that this cemetery is listed as something other than a cemetery. I understand that these codes fulfill some type of bureaucratic taxing purpose, but how, when, and why was this choice made? It reminds me of the disrespect for the dead that I saw when I did archaeology on a reservation in Connecticut, gravesites treated as landmines to navigate around instead of places of respect. Maybe I’m too woke, but I like respecting the dead.

I felt an early morning call to walk with providence and I made my way over to the property, letting my intuition take the wheel and guide me. The Sun Chronicle article I read said that one of the State Hospital’s old groundskeepers, George Dodge (1928-2012), was a resident of the street that the property is located on. He felt like the patients buried there deserved better that to be forgotten, he would mow the lawn and take care of the general upkeep after the closure. Legally, the properties became the responsibility of the Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance (DCAMM). When asked about the status of the cemeteries, former deputy director of the Division of Capital Asset Management Robert Cohen noted “we’re hoping a developer will take care of the maintenance and be responsible for the upkeep,” all the way back at the turn of the century 2000. He said they would “like to see it kept as a better maintained location,” and add a couple amenities, like a few bushes and a plaque. The plaque is there, the bushes are there. The graves do not appear to be maintained, but this surface level of respect is still a win. Whose responsibility is it to take care of these cemeteries? Can private developers be trusted to maintain burial grounds or does that obligation fall to family members and neighbors when the Commonwealth doesn’t directly handle it?

Before the property became an active topic for redevelopment a couple decades ago, Eagle Scouts were the ones to clean up the poorly maintained cemeteries. This lack of care and effort was visible to everyone who looked, so it inspired state Senator Frederick Berry and state Representative Theodore Speliotis to introduce a bill to create funds for the “preservation and memorialization of existing cemeteries at current and former public facilities”. Senate Bill 1530, later 2315, aimed to use 0.5% “of the sale or lease of state properties to go toward the establishment of a centralized fund that would oversee the upkeep of any cemeteries on state facility properties” until the end of time. “An Act relative to the identification of burial grounds and cemeteries on certain state-owned lands” would have created The Commonwealth Public Facilities Burial Ground and Cemetery Preservation Fund.

This fund would have:

•Identified, restored, protected, maintained, and memorialized cemeteries on past, present, and future state-owned lands

•Systematically recorded all burial grounds on state lands •Accounted the names of the individuals in state-owned burial grounds

•Funded itself through the neighboring properties that were currently being sold off

This act bounced around the Massachusetts State House with claims that it “ought to pass” for about a decade with minor alterations before disappearing on the Governor’s desk. It was supported by the Department of Mental Health, several advocacy groups, and members of the Senate and House.

Today the land sits in an unaltered state, a new limbo. The Medfield State Hospital cemetery was in a similar position until another Eagle Scout troop cleaned up the area and started the Medfield State Hospital Cemetery Restoration Committee in 2005. Their cemetery sits with care and maintenance from a public organization while the Foxborough State Hospital cemeteries rely on acts of kindness.

It is almost like the patients are facing the same cycle of attention and neglect that they suffered through while alive. They will have decades of struggle like before the Kirkbride Plan, a period of stability and structure, then several more decades of decline until they are economically relevant again. When I visited the graveyard it was early in the morning. The plaque made a note about the State Hospital’s humble beginnings as a place for recovering alcoholics. As someone who has been surrounded by those suffering from addiction and arguably suffered myself, it was extremely humbling to see how the vulnerable are treated in death. Their graves were marked with numbers, not names. Their identities were stripped from them just like their structure for reform was. I let intuition guide me and I wandered around the cemetery for a few moments, looking at the half-submerged grave markers with moss obscuring the numbers. I heard somewhere that my own great grandfather, a man who struggled, was in a similar place somewhere in Rhode Island. Leaving only a grave marker with an identification number.

What is our current philosophy for treating the unwell? Do we give them space for development or do we constrict and neglect them? Mental illness and addiction are demons that lean on the periphery for a lot of the population, and they can have a generational impact. Investing effort and resources into programs to assist the vulnerable and pull them out of dark places is a moral obligation and in the long-run it will prove to be economically viable. I hope that this new interest in the maintenance status of these forgotten cemeteries will lead to an elected official reintroducing a bill to memorialize those that we left behind. For the time being, organizations like the Medfield State Hospital Cemetery Restoration Committee and Danvers State Memorial Committee continue to fight for these unidentified patients and their legacy. Everybody deserves a dignified resting spot, and as the immediate family members and ex-patients pass away, we can not let this effort die down.

Just like the plaque says at Medfield State Hospital’s cemetery – “Remember us for we too have lived, loved and laughed“.